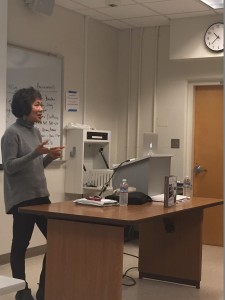

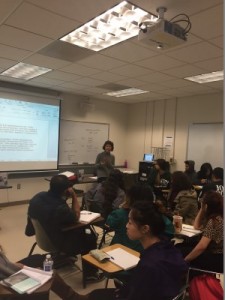

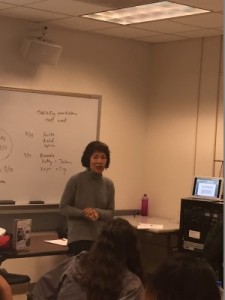

This past Thursday, I attended two sections of History of Asians in the U.S. class, under San Francisco State University’s Asian American Studies, College of Ethnic Studies. Lecturer Kei Fischer had her students, who were mostly freshmen, read Chapter 11 of A Village in the Fields, which chronicles the beginning of the Delano Grape Strike, and invited me to discuss the Filipino American contributions to the farm labor movement.

Kei had assigned the students an oral history project in which they had to interview someone about their history and present to the class. Before I spoke before each class, three students presented. Since most of these kids are eighteen or nineteen years old, their parents’ immigrant stories from the mid-1990s were fascinating to me. Some parents didn’t know English and had to learn, they had to struggle with assimilation and isolation, and the American Dream was through their children. At the same time, there were obvious generational differences, but I realized that the immigrant experience is still a journey fraught with anxiety and hope. I told Kei after the first class that it was a wonderful project to assign. And I told the second class how important it is to capture their families’ stories.

After the student presentations, Kei showed Marissa Aroy’s documentary, Delano Manongs: The Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers Movement. No matter how many times I see the documentary, I am always moved by the images and the stories. As I got up to speak, I reminded myself not to expect an engaging group of students as I had when I spoke last fall at Professor Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales’s Filipino/a Literature, Art, and Culture class. For one, these students read the entire book. And just as important, most of them were juniors and seniors. The maturity level is quite stark between those in their first year of college and those getting ready to graduate. Plus, the juniors and seniors have taken many more AAS courses and their awareness is markedly more advanced.

I’m not really sure how many of the students (I’m guessing there were 40-50 students per class, which was heartening to see) actually read the chapter because none of the questions were directed at anything that happened in that chapter. As expected, none of the students were aware that the Filipino American farm workers had started the strike. So for me, my goal was to share that rich history with them. Whereas before I came on campus, I fretted that it had been several months since I’d last spoken about the book and the history, I went into full-speed-ahead mode.

I shared a lot of buried stories, as well as the general history. For example, Johnny Itliong, Larry Itliong’s son, told the story back at Bold Step: The 50th Anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike in Delano last September, of how he had approached the director Diego Luna to ask about historical inaccuracy in his 2014 feature film about Cesar Chavez. Johnny asked Luna why his father was standing in the background and not at the table when the 28 growers finally sat down to sign union contracts. In the scene, which I have not seen but heard plenty about, Larry Itliong is a bystander in the historic signing, while Chavez is penning the contracts on behalf of the farm workers. Luna’s response was that he took artistic license and the film was about Chavez and not the Filipinos. I stressed to the class that when you don’t know the history and you watch a film about a famous person, you accept what happens, especially the details, as having actually happened. I let the students know that, in fact, Itliong’s union and Chavez’s organizing committee had not merged as the United Farm Workers Union yet. Itliong represented a true union, while Chavez was head of an organizing committee with no union powers. Therefore, Itliong’s signature was binding, not Chavez’s.

I stressed that there is still tension between the two groups, especially now that the Filipino-American community is coming forward after so many years to tell their side of the story, to set history straight, and to gain recognition for the Filipino-American labor leaders that is rightfully theirs. Coming forward with this mission means not tearing Chavez down. It means giving credit where it rightfully belongs. And it means telling history accurately. It’s not just Filipino-American history. It’s American history. Let’s all be educated. Let’s all be given the full information. Let’s all be informed.

More so with the second class, I saw many heads nodding as I spoke. As the second class was dismissed, I wondered what impact my presentation had on the students. If they didn’t know this part of Filipino-American history, they did so now. Kei entreated both classes to share the knowledge, spread the knowledge about the contributions of Filipino-American farm workers to the farm labor movement. That’s the beginning. And though I was sure that many had not read my chapter, I came away from the two presentations with satisfaction that perhaps 100 students will create a ripple effect and more people will know our history.

As Jose Rizal was credited (in other places not, but I’m giving it all to Rizal) as saying: “No history, no self; know history, know self.”

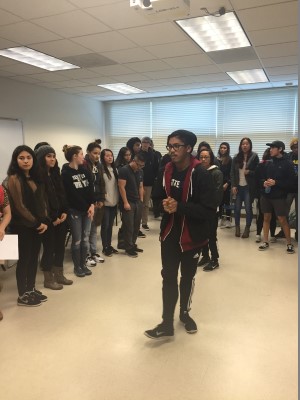

To conclude the day’s lesson, Kei invited Lennard, the history coordinator for the largest Pilipino student group on campus – the Pilipino American Collegiate Endeavor (PACE) – to teach the students about the Unity Clap and Isang Bagsak. The Unity Clap is a gesture that mimics “the progression of a heartbeat through collective, synchronized clapping.” The Unity Clap “overcame the language barrier between Latino and Filipino members of the UFW” in the 1960s. Isang Bagsak literally means “one fall” in Tagalog. But figuratively, the term means “things can’t get done if people don’t communicate and work together.” When someone calls out Isang Bagsak, the clapping ends with one unified and spirited clap. And that’s how the class concluded.

Patty, this sounds so exciting. The “ripple effect” from your talks, as well as from Village in the Fields itself, is profound!

Thanks so much, Steve!