Back in December 2016, Oliver Rosales, Professor of History and Coordinator of the Social Justice Institute at Bakersfield College, and Andrew Bond, Associate Professor of English at Bakersfield College, reached out to a number of people to write a letter of support for a National Endowment for the Humanities Community Colleges grant they were applying for. If awarded, Oliver and Andrew would use the grant “to provide Bakersfield College faculty the opportunity to work with visiting scholars and authors in a seminar-style setting, as well give the authors a chance to do a public presentation on their work.”

Andrew’s expertise is in Asian-American literature, although he told me he was learning more about “the historical Asian-American presence in the Central Valley through the historical work of Carey McWilliams and literary works based in and/or written in the region.” Andrew noted that “the goal of the lit year is to cover the literary and multicultural Central Valley.” The proposed series of seminars and speaking events were slated to include representations of agriculture and labor in literature, Latino/a literature and place-based pedagogy, autobiography as a pedagogical tool in composition, and regional Asian-American cultural and literary histories.

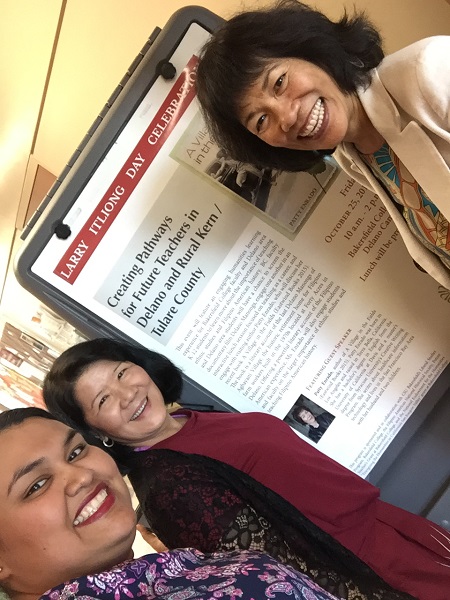

While I was really excited about the program, the timing worried me. They had reached out to me months after the 2016 election, and it seemed that the current president was systematically tearing down arts and cultural programs, among other atrocities. Amazingly and happily, in July 2017, they received word that their grant proposal was accepted and would cover three years of programming. My participation in the program was slated for the fall 2019 semester, specifically October 25th, which is Filipino labor leader Larry Itliong’s birthday and traditionally the date of many celebrations around the country known as Larry Itliong Day.

The event began after breakfast with a tour of historically significant places related to the farm labor movement in Delano. My Auntie Leonora Carreon joined our group, which included Bakersfield College NEH faculty cohort members; Yesenia Garcia, a former student of Oliver’s who also brought special guest Javier Cardena, a Delano resident who had worked with Chavez and the United Farm Workers and was donating his personal collection of newspaper articles, photos, and other memorabilia of the grape boycott to Bakersfield College’s Digital Delano Project; and Alex Edillor, president of the Delano chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), who served as our tour guide. I had met Alex four years ago Labor Day Weekend when I came down for the event “Bold Step: The 50th anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike.” Alex moved to Delano when he was very young and remembers the events leading up to the strike and the strike and grape boycotts. Alex told a very moving story that I want to share. His mother, who worked on one of the farms, protested the wages assigned to the female farm workers, which were lower than the wages for the male farm workers. She wrote a letter of protest, which found its way to the grower. The grower shared the letter with his wife and asked if she thought the wage disparity was unfair. Then he went to the fields and asked who had written the letter. All the female workers pointed to Alex’s mother, who stepped up unflinchingly. The grower told her the story of reviewing the letter with his wife, whose response was an unequivocal “yes” — the wage disparity was unfair. As a result, the grower matched the wages of the women to those of their male counterparts. Only on that farm were the women being paid on par with the men. We can all be proud of Alex’s mother’s courage to take a stand for what’s right, and especially at that moment in time, before the Great Delano Grape Strike.

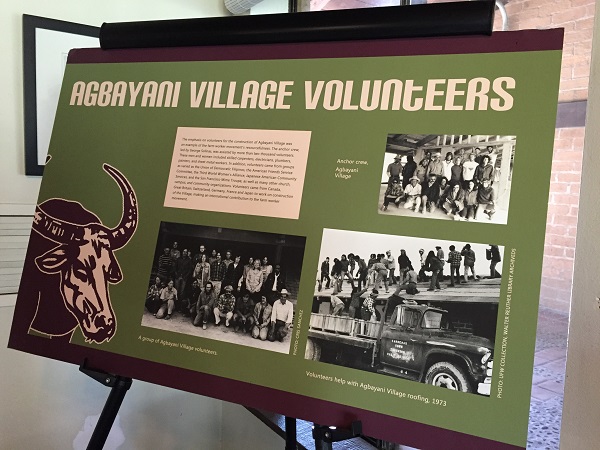

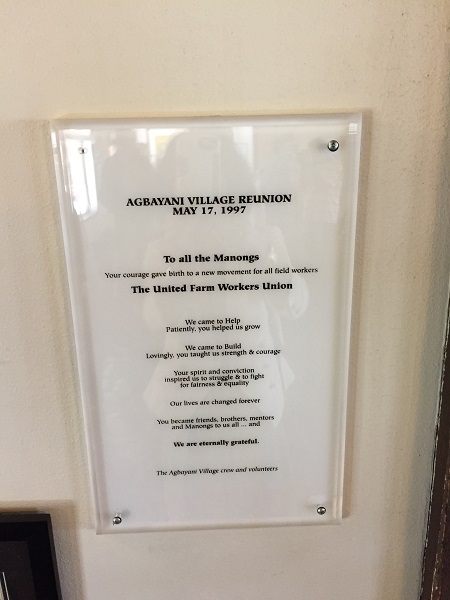

We visited the Filipino Community Cultural Center, where the striking farm workers, comprising Mexican, Filipino, Yemeni, Puerto Rican, and other groups, sat down together to eat meals. We drove by Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, where Chavez took a vote to join Larry Itliong and the Filipino farm workers who struck, and Larry Itliong’s grave in North Kern Cemetery. Then we headed to Agbayani Village, which is the setting for the opening and closing of my novel, A Village in the Fields. The last time I set foot on the grounds of Agbayani Village was for the 50th anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike in September 2015. But every time I visit, I find something new to examine, behold, and appreciate.

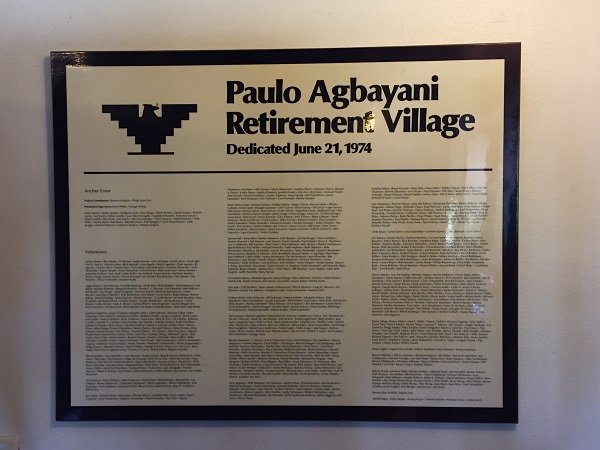

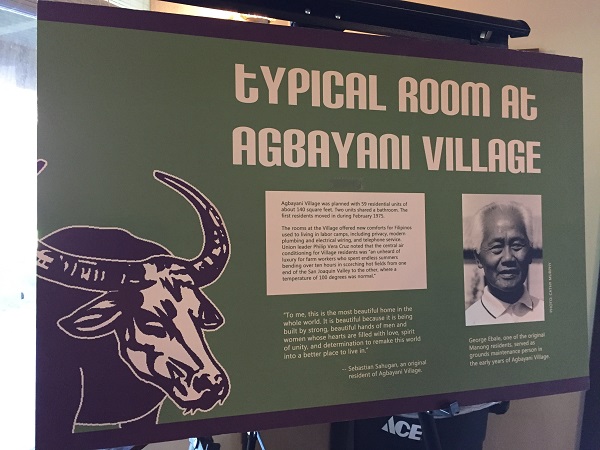

The Forty Acres (10701 Mettler Avenue, Delano), which Agbayani Village is a part of, was dedicated in 2011 as a National Historic Landmark that commemorates the farm worker movement’s role in U.S. history. The Forty Acres comprises the Tomasa Zapata Gas Station, the first building constructed on the property and one that provided gas and auto repairs for the farm workers; Roy L. Reuther Hall, which swerved as the union’s headquarters when it was dedicated in 1969; the Rodrigo Terronez Memorial Clinic, dedicated in 1972 as a medical clinic; Richard Chavez Memorial Park; and the Paulo Agbayani Village, which continues as a source of low-cost housing in the community.

Many of the Filipino farm workers who were single and older and had participated in the 1965 Delano grape strike moved into the facility when it opened in 1975. One unit, open to the public, has been preserved to honor the site of the 36-day fast by Cesar Chavez in 1988 to highlight the use of pesticides on farms that impacted the health of many farm workers. As you walk into the room, called “the fast room,” you note the simplicity and sparseness of the furnishings, and come away with a feeling of awe, a feeling that you were witness to and have been imbued with Chavez’s spirit.

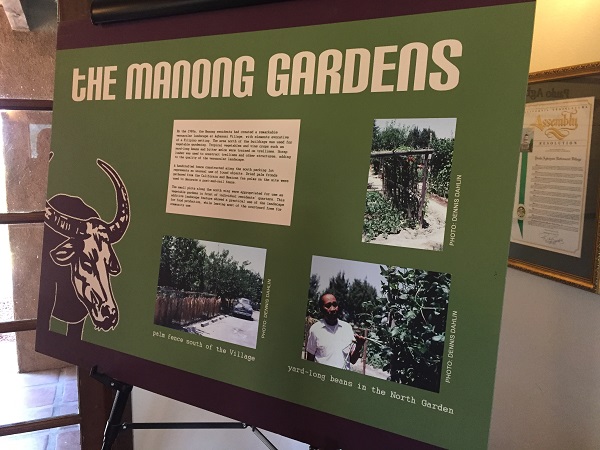

In addition to the private rooms for tenants, the Village boasts a kitchen and dining hall and main room with a fireplace built with local river boulders. The public rooms feature many framed photographs and photo montages documenting the labor leaders and the strikers, capturing them in action during the strike, the boycott, and the building of the village. I have noted before that when I first started my research for my novel my relatives informed me that we were related to the last manong of Agbayani Village, Fred Abad. I don’t remember him at all, although I have fond memories of Uncle Alex Abad, who was also a bachelor who worked the fields and related to Manong Fred. My relatives also told me that Manong Fred was sharp as the proverbial tack and had passed away a few months before I began my research journey.

As we were leaving Agbayani Village, a busload of high school students from Castro Valley, in the Bay Area near me, had just arrived. The students were in the area to look at colleges and had an opening in their schedule. The teachers had heard about the historical landmark and added the tour to their itinerary. Alex informed us that he gives 5-6 tours a year, mostly for college students from UCLA, Cal, Stanford, and San Francisco State University, who have heard of Agbayani Village. I hope the word spreads to more history and Asian-American Studies professors and students at other colleges, so that the history of the Delano Grape Strike and the farm workers can be experienced first hand and greater knowledge of the farm worker movement can be shared widely.

After the tour, we arrived back at the Delano campus of Bakersfield College. The event, “Creating Pathways for Future Teachers in Delano and Rural Kern/Tulare County,” was tailored for the 60 or so Filipino-American students from Delano’s four middle schools to have them consider teaching as a career and to learn about the importance of teaching/studying ethnic studies and Filipino American history. After opening remarks by Oliver, Andrew, and Abel Guzman, Director of Rural Initiatives at Bakersfield College, Marissa Aroy’s documentary, Delano Manongs: The Forgotten Heroes of the UFW, was screened. I have seen Marissa’s documentary many times, but I never tire of watching it and being proud that the film continues its journey of awareness and education for many students and groups. After viewing Marissa’s documentary, the adults sat with small groups of students during the lunch break. I sat with two six-grade and one seventh-grade young men. I asked about their academic interests and passions, and if they were brought up with a college culture at home. One of the students told me both his parents weren’t able to finish college because they couldn’t afford it and now his parents are working the fields. I shouldn’t have been taken aback by his story, but I admit that I was. Being second-generation Filipino Americans, my sisters, our cousins, and I were brought up to appreciate education and the value of a college education. Going to college was indoctrinated in us, and that tradition and cultural indoctrination continues in the third and fourth generations. But I’m forgetting that there are new Filipino immigrants who have arrived in the last couple of decades, and they are facing the same or similar issues that our parents endured. My conversation with this particular student made me think I was on the right path with the topic of my presentation.

After lunch, I explained that I titled my presentation “Nurturing Our Village in the Fields” because we — everyone at that event — share the same roots and thus come from the same place, and we need to nurture everyone in our village in order for all of us to succeed. I talked about my own journey of finding my roots when I took Asian-American Studies classes while at the University of California at Davis as an undergraduate. Two things happened: When I took those classes, particularly the Pilipino Experience class, I was able to contextualize facts about my father that had contributed to the tension that had existed in our relationship since I was young — he only had a second-grade education, he was 55 years old when I was born, and he was from a lower socio-economic class in the Philippines than my mother. I learned that the experiences of the first wave of Filipino immigrants who came to America in the 1920s mirrored my father’s experience. He had a second-grade education because he was needed to work in the family rice fields. He was a victim of racism and the anti-miscegenation laws in America that prevented him from interracial marriage. It wasn’t until after WWII, when he received his citizenship, that he could return to the Philippines and marry a Filipina and legally bring her to the States. I came to understand him and appreciate his courage to go to America (the only English words he knew at the time were “yes” and “no”) to, as he once shared with me, “change his luck.” So taking Asian-American Studies (Ethnic Studies overall) set me on a path to understanding my history and my father’s history. And it brought us closer together. I was able to appreciate my mother’s history as well, and by the time I graduated from Davis, my oldest sister, my mother, and I returned to the Philippines to get back in touch with our roots.

The other thing that happened as a result of taking Asian-American Studies was finding my voice as a Filipina-American writer. I was studying and trying to emulate the famous writers at the time. They were all named John, it seemed — John Updike, John Cheever, John Steinbeck. The others included Ray Carver, James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway. In other words, I was studying the canon at the time — all-white males, with a few white women sprinkled in. My writing was stilted and inauthentic. I wrote a short story about my relationship with my father, and my creative writing professor told me that this story rang true, was heartfelt, and the writing flowed. It wasn’t until I went to Syracuse University in upstate New York, far away from home, that my subconscious homesickness made me see my hometown and my family and relatives in sharp relief, and I began writing about them in earnest. This period of my writing about my heritage set the stage for embracing the story of the manongs and wanting to tell their story and the story of my Filipino community in my hometown of Terra Bella when I returned to the Bay Area after graduating from Syracuse University.

Circling back, Ethnic Studies, Asian-American Studies for me, is critical for students of color connecting with their history. With that knowledge and context, students of color can achieve greater awareness and appreciation of their predecessors and the struggles they overcame, which has contributed to their ability to dream big and build that foundation to reach their full potential. Stanford University conducted a study, which was published in 2016, and found that at-risk students who took Ethnic Studies classes at a San Francisco high school had better attendance and improved academic performance. I did a little research on where California stood in terms legislating Ethnic Studies as a high school requirement for graduation. The bill, which was co-authored by Rob Bonta (D-Alameda), our one and only Filipino-American legislator in California, has been termed a two-year bill in order to address the concerns of inclusion by various ethnic groups in the state. Some school districts have taken it upon themselves to mandate Ethnic Studies as a high school graduation requirement, while others have expanded Ethnic Studies classes across high schools. For example, in 2014, only 19 schools in the Los Angeles USD offered Ethnic Studies, but last year that number jumped to 83 schools. Progress is good.

My research, however, surfaced some troubling news. El Rancho Unified School District in Pico Rivera, Calif., was the first school district in California to mandate Ethnic Studies as a requirement for graduation beginning with the class of 2016. But a group of parents have fought back, which is unfortunately a reflection of the current times, and have rotated out school board members and forced an Ethnic Studies teacher, who was well liked by students, to resign. They argue that the teaching of Ethnic Studies has become politicized. I would argue, how can it not be political? The struggles of immigrants and natives haven’t been well documented and disseminated in our history books and in literature and in other areas. We are surfacing that now and fighting for a seat at the proverbial table. All of that is inherently political. It’s the nature of the beast. We have made progress, but it’s not ever enough. My point is that while we may fight for a right and we may rejoice in that right being gained, we can never rest. We must always be vigilant. What was gained must be protected. Every student, especially students of color, deserves to be offered a path to self-discovery and discovery of all of our histories, not just the history that a small group of gatekeepers determine is the only one to be taught and to be taught as if it were the singular source of truth — because it is not.

I touched on other things in my presentation — the value of community college and my advice to students to please not go into debt to get a college degree, among other things. I closed with my “challenge” to the students to keep nurturing our village in the fields (our rural hometowns):

*Find a mentor, become a mentor (in or outside the classroom)

*Find teachers who motivate and inspire

*Read, write, and think critically: It will serve you well no matter what you study

*Honor your family’s history by documenting it (All of our histories are important, and our voices are vital)

*Take an Ethnic Studies class in high school, college

*Consider attending community college (Transfer Admission Guarantee, or TAG, Program) (save $$$)

*Always be vigilant about keeping the importance of Ethnic Studies and our histories front and center

*Advocate for your community: Give back because “We rise by lifting others”

Thanks again to Professors Rosales and Bond for an engaging day of activities and discussions. I want to take a moment to acknowledge that the program was sponsored by and in collaboration with CSU Bakersfield’s Liberal Studies Program, Bakersfield College, FANHS, Future Teacher’s Grant at Bakersfield College, and the National Endowment for the Humanities “Energizing the Humanities in California’s San Joaquin Valley” grant at Bakersfield College. I enjoyed meeting the students and faculty, making new friends and acquaintances. I love coming down to the Central Valley, which is always home to me in my heart.

Lastly, I want to give a shout-out to Bakersfield College’s President, Sonya Christian, who mentioned the event in her November blog, and especially to Oscar Camacho, a Delano youth reporter, who wrote an article about the event for the local Kern Sol News. Looking forward to seeing his byline in new publications in the future!